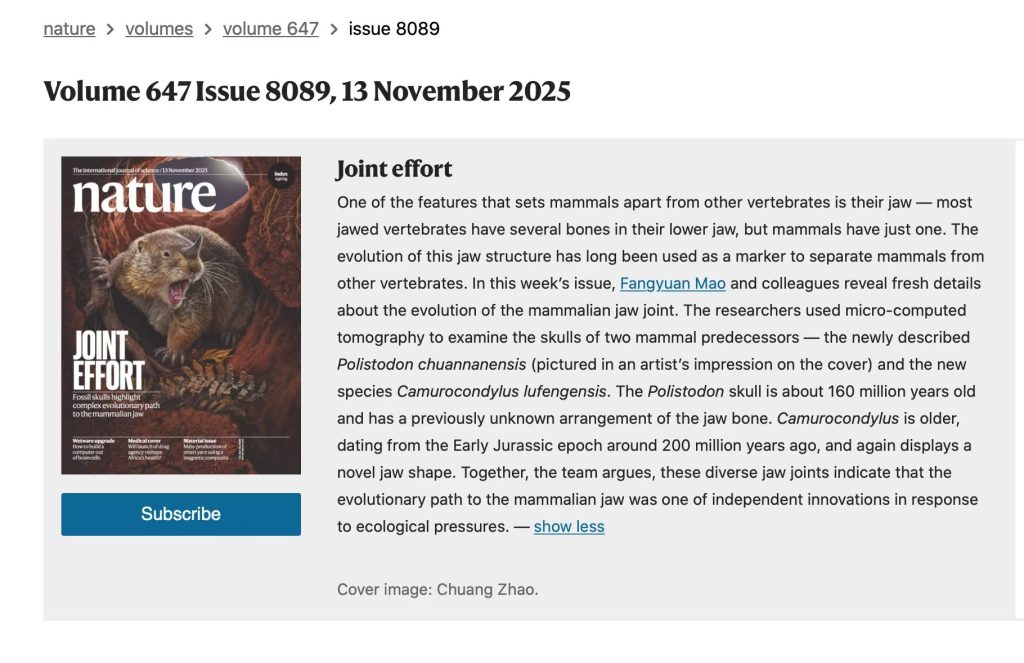

At the invitation of paleontologists Meng Jin and Mao Fangyuan, the scientific artist Zhao Chuang provided scientific and artistic support for their ongoing research on Polistodon chuannanensis. Following the publication of their paper in Nature on November 13, 2025, Zhao’s artwork was selected as the cover image for that issue.

Zhao then shared with us the process behind creating the artwork.

“The initial restoration employed a vertical composition, with a perspective looking upward from the bottom of the den, depicting a Polistodon chuannanensis startled, fleeing backward while vocalizing and communicating with its companions inside. Conceptualizing this scene as the main focus is because the specimen mainly preserves the skull. This angle helps emphasize the head’s key features, especially its iconic nasal horn. Including the open mouth to vocalize helps show the shape of its teeth.

The first sketch portrayed the head held higher to display the maxillary teeth. However, the mammal’s thick upper lip made this movement appear awkward upon further detailing. It was then adjusted to a head-down position, gazing into the depths of the den. Meanwhile, I added some common Jurassic fallen leaves at the entrance, like ginkgo and withered ferns, along with exposed tree roots from the soil to indicate the animal’s size. During the drafting stage, I thought about placing a carnivorous dinosaur outside the den for a dramatic effect. However, fossil records of carnivorous dinosaurs from Dashanpu are often incomplete and less recognizable. So, I ultimately included Gigantspinosaurus, a dinosaur unique to Dashanpu in Sichuan, into the restoration.”

“During the creation process, the researchers proposed enlarging the scene to showcase the animal’s intricate burrow system and behaviors. So, I extended the composition downward and to the right, following the passage’s path, to create an underground cross-section. At the center of the scene is a chamber used for storage and resting, which I filled with a litter of pups and scattered tubers — these elements are backed by relevant evidence.

Since burrowing animals are protected by their dens, I pictured the pups as chubby with softer fur and emerging nasal horns. For their sleeping posture, I envisioned them like domestic dog puppies, snuggling for warmth, with a few lying on their backs to look more relaxed and defenseless.

On the right side of the scene, two passages lead into the chamber. One passage shows a mother visiting her pups. The female forms a family unit with the male at the den entrance and is used to showcase the side profile of the animal. This female’s nasal horn is depicted as smaller than the male’s, and the proportions of her skull strictly follow the structure of the specimen, with compressed parts reconstructed. Since no postcranial bones were available, her body proportions were based on those of Fossiomanus senensis, which features short legs, a short tail, and sharp claws.

Additionally, the soil in the scene reveals many tubers that serve as a food source for the animal. Although no plant fossils have been discovered at this site, I depicted them with a morphology similar to that of modern ferns, such as the western sword fern.”